How HTTP Headers Work

HTTP headers are small bits of text that are sent back and forth between clients and servers.

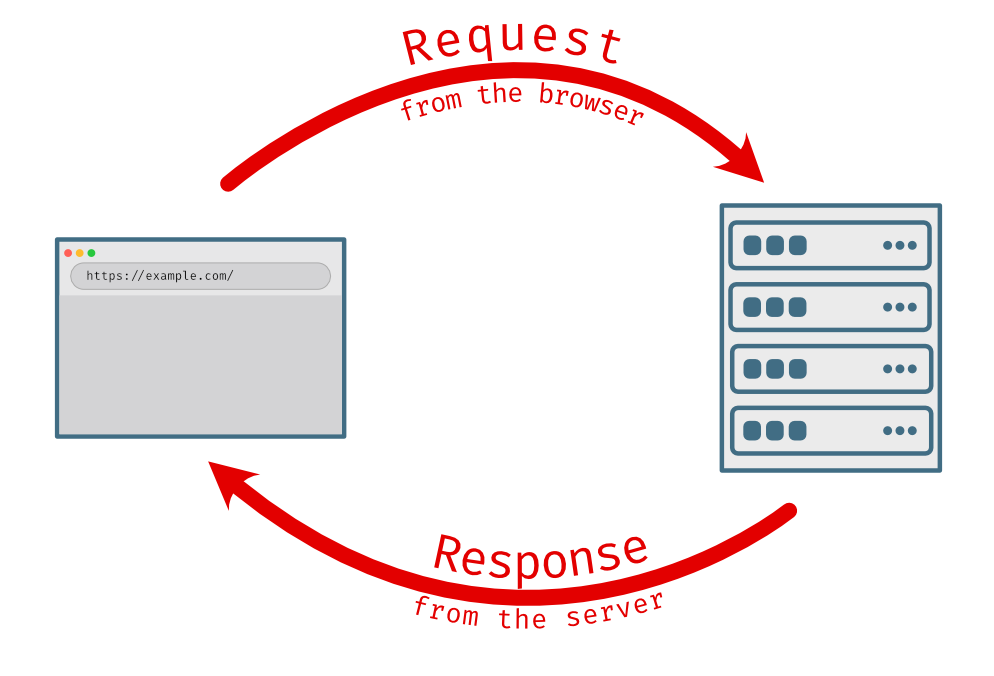

Web clients (like Web browsers) make requests for information, and Web servers send back responses.

Under the hood, those requests and responses are prefixed by some hidden data that helps the machines communicate with each other. The HTTP headers are in that hidden data.

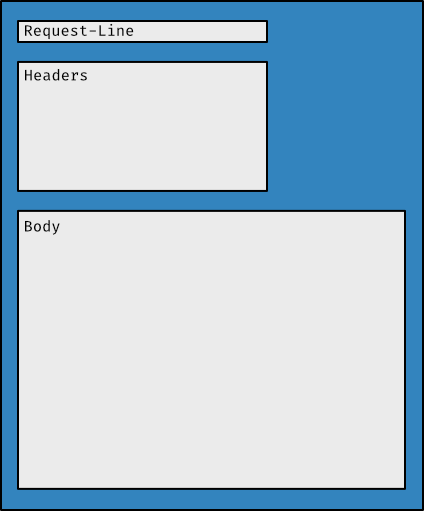

You can think of the HTTP request kind of like a package that you’re going to deliver to a remote computer. The package has two labels with delivery instructions: a Request-Line and some headers. The contents of the package are in the body section.

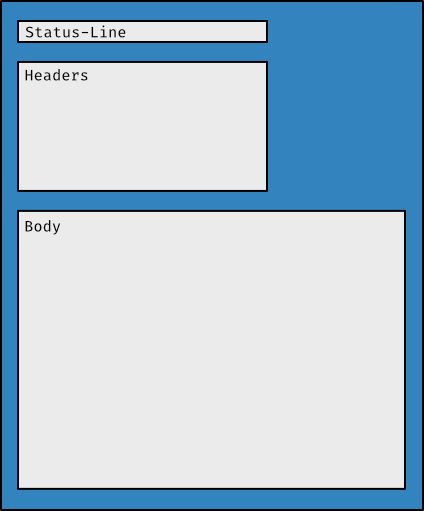

The response is similar. Typically, there are two labels and an optional body.

Some of that hidden data is useful for SEO and Web development, such as HTTP status codes (e.g., 200, 301, 404), caching, and cookies.

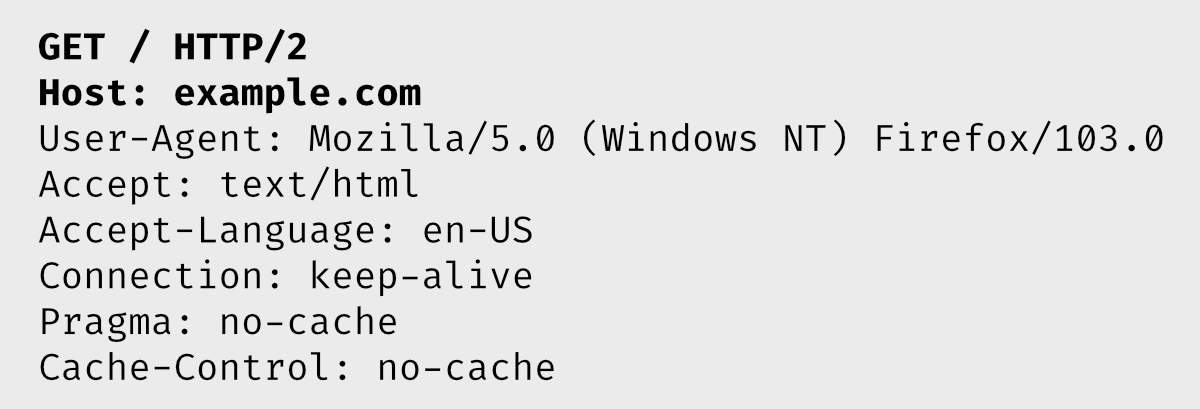

As a quick preview, the request headers below tell the server what page to fetch (/ = home page), what kind of browser is making the request (Firefox on Windows), what kind of content to send back (HTML), and what language the visitor uses (US English).

There are several versions of the HTTP protocol. The headers between the different versions are similar.

We will take an in-depth look at HTTP headers below and talk about why they are important in SEO and Web development.

What Are HTTP Headers?

When your browser makes a request for a Web page, it quietly sends a small block of text information to the website’s server that looks something like this:

GET / HTTP/2

Host: example.com

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64; rv:97.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/103.0

Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,image/avif,image/webp,_/_;q=0.8

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.5

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate, br

Connection: keep-alive

Pragma: no-cache

Cache-Control: no-cacheThat block of text contains the two package labels mentioned above.

Let’s take a closer look.

The Request

The first line of the request is called the Request-Line.

It says “GET me the root path (/) of the site using the HTTP/2 protocol”:

GET / HTTP/2(HTTP/2 is just version 2 of HTTP, which is the communication system that browsers use to fetch Web pages.)

A directory or folder always has a trailing slash, so the root of every website is always represented by a trailing slash, as in the above example.

If you were requesting example.com/about, then the first line of the request headers would look like this:

GET /about HTTP/2The other lines in the block are the HTTP headers.

HTTP headers come in key-value pairs. The part before the colon is the field label, and the part after the colon is the value of that field.

So looking at the first header, we can see that it’s saying that the host is example.com:

Host: example.comand that the User-Agent is Firefox version 103 on Windows 10:

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64; rv:97.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/103.0and that the browser would like content in English:

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.5There are many possible headers, and you can even create your own. We’ll look at those more closely when we put together some Web servers from scratch.

The Response

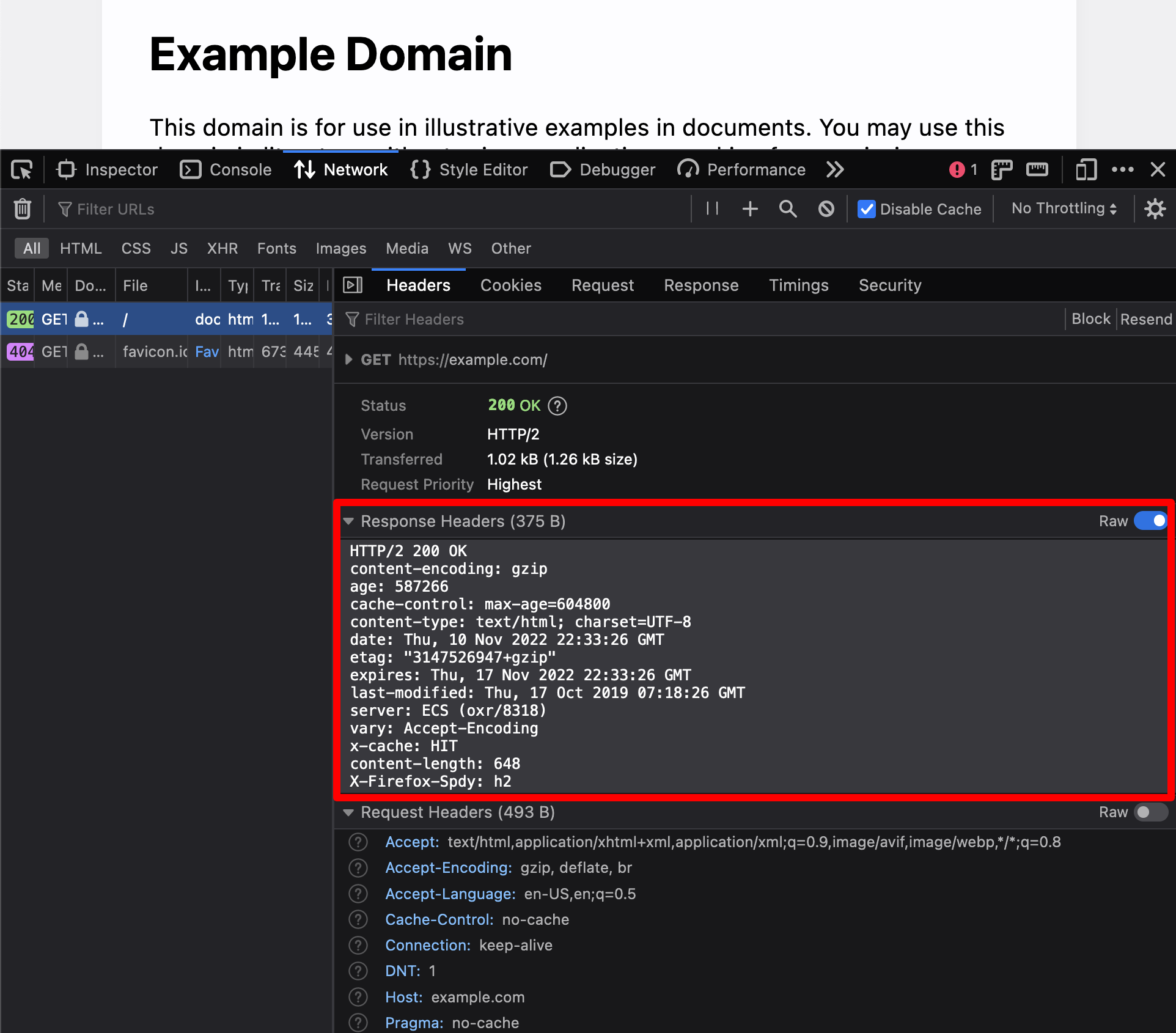

The server then responds back with its own response headers that have instructions for the browser.

The first line of the response is the Status-Line.

HTTP/2 200 OKThat says that the server is responding with HTTP version 2, and that the request was okay. 200 is the HTTP status code for “everything is good”.

After the Status-Line come the HTTP headers. They are in key-value pairs, just like the request headers. It’s hidden information that helps the browser and server communicate like “I’m sending you this file in HTML format” or “this document was last modified yesterday”.

Here are a few sample response headers:

content-encoding: gzip

age: 586449

cache-control: max-age=604800

content-type: text/html; charset=UTF-8

date: Thu, 10 Nov 2022 22:19:49 GMT

etag: "3141592653+gzip"

expires: Thu, 17 Nov 2022 22:19:49 GMT

last-modified: Thu, 17 Oct 2019 07:18:26 GMT

server: ECS (oxr/8318)

vary: Accept-Encoding

x-cache: HIT

content-length: 648

X-Firefox-Spdy: h2How to View HTTP Headers

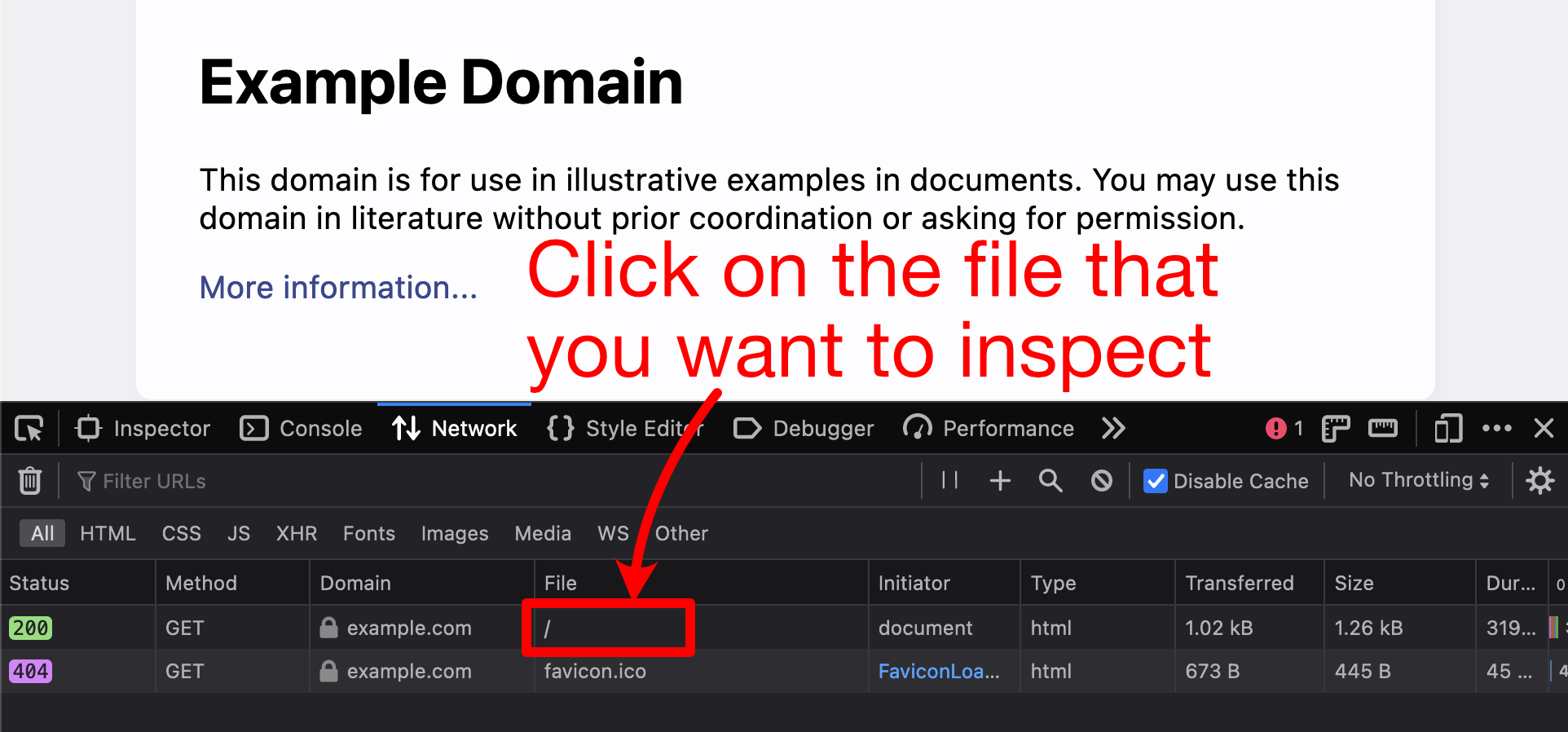

You can view the HTTP headers sent with a request by opening up the browser’s network tab. On many computers you can open it with F12 or by right-clicking on the page and choosing “Inspect”. In the window that opens, choose the tab that says “Network”.

After the network tab is open, reload the page and look for the path of the page you want to inspect. In this case it’s the root of the domain (which is indicated by a slash character: /).

Clicking on that row opens a sidebar with the HTTP header information:

Takeaways

Things that you should remember from this section:

- There are three parts to HTTP requests and responses: an initial line, the headers, and an optional body.

- The initial line is a

Request-Linefor requests andStatus-Linefor responses. - HTTP headers are hidden bits of information that Web clients and servers use to communicate with each other.

- HTTP headers come in key-value pairs. The part before the colon is the field name, and the part after the colon is the field value.

- HTTP headers can be viewed with a browser’s network tools or with a program called

curl.